|

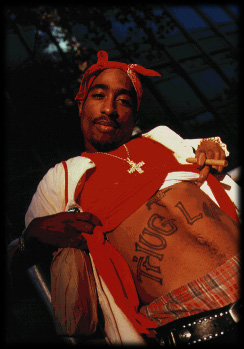

Day Three: Fearing gang-related

violence, hospital authorities step up security. Between

UMC security, LVPD, and Death Row bodyguards, the trauma

unit is all badges, brawn, and walkie-talkies. Outside,

a local Channel 3 news van backfires twice and everybody

in earshot drops to the ground. At about 8 p.m. police

and Tupac's crew get into a shouting match that results

in people getting handcuffed and detained by police.

LVPD's Gang Sergeant Cindi West calls it "a misunderstanding."

Rumors abound. Depending on who you ask,

Tupac is either on his way to the morgue or in intensive

care puffing on a cigarette. In truth, he's alive but

experiencing respiratory trouble. Surgeons decide to

go in a second time and remove 'Pac's shattered right

lung. "You can live with one lung," says Dr.

Jonathan Weissler, chief of pulmonary and critical care

medicine at Southwestern Medical in Dallas. "And

after a while you can live quite well with it."

After hours of unconsciousness, Tupac

momentarily opens his eyes. Hearts are lifted.

Day Four: The entire hip hop world

is turned on its ear. Overzealous reporters suggest

that the shooting is tied to the East Coast- West Coast

rivalry. A few speculate that it may be gang-related.

Among the names being thrown about are the Notor ious

B.I.G. and Mobb Deep (who are both entangled in protracted

lyric feuds with Tupac), Las Vegas Crips, Los Angeles

Crips, even Death Row employees. At least one Bad Boy

Entertainment staffer receives death threats, and the

New York-based label cancels a scheduled appearance

of some of their artists.

|

"That this is gang-related is still

pure speculation," says Sergeant Manning. "We

have to run by facts." The entire Death Row organization,

according to one employee, has been put under a gag

order by higher-ups. LVPD, frustrated by the lack of

coopera tion from Tupac's camp, complain to the press.

"The problem is a lack of forthrightness,"

says Manning, barely concealing his disgust. "It

amazes me when they have professional bodyguards who

can't even give an accurate description of the vehicle."

Meanwh ile Suge, who was released from the hospital

with minor head wounds, is nowhere to be found.

In the trauma unit there's meditation

and prayer. Tupac's aunt, Yaasmyn Fula, a tall, regal

woman, removes her glasses and wipes her puffy eyes.

"I'm just really, really tired," she says

quietly. Afeni Shakur, 50, a woman of small frame and

formidable grace, looks about the same. The former Black

Panther who 'Pac calls Mama seems to carry the weight

of the world upon her small shoulders. Visiting hours

are almost over and she returns to the hotel for an

hour or two of restless rest. 'Pac is still in critical

condition.

Family members silently get into a plain

blue Chrysler. An older man wraps his arms around Afeni,

and she leans in heavily as the car drives away.

Day Five: The morning brings news

of a murder in Los Angeles. A Compton bodyguard, who

police say is connected with the Southside Crips, has

been shot in his car and pronounced dead at Martin Luther

King Jr. General Hospital at 9:53 a.m. The rum or is

that the homicide was payback for Tupac being shot.

"Someone just drove up alongside and blasted him,"

says LAPD homicide detective Mike Pariz. "This

is only the beginning," says a Compton resident.

"The gang shit is about to be on."

Suge makes himself available to the LVPD

for questioning. Investigators review a videotape from

the MGM taken the night of the Tyson fight, which reportedly

shows Tupac and others in a confrontation with an unknown

black man dressed in jeans and a T-sh irt. "This

happened at approximately 8:45 p.m.," says Sergeant

Manning. "Kicking and punching were involved."

Authorities won't reveal whether Tupac or Suge personally

assaulted the man. Once police officers arrived at the

scene they asked if the victim w anted to file a complaint.

He said "Forget it" and walked away. Officers

never got a name. "There is no reason to believe

that these incidents are at all connected," says

Manning.

Day Six: Tupac, his eyes closed

and his remaining lung inflamed, ("Ready to Die,"

cont.) struggles for his life. He's connected to a respirator,

his body convulsing violently at times. Doctors induce

paralysis for fear of 'Pac hurting himself. D r. John

Fildes, chairman of the hospital's trauma center, gives

him a 20 percent chance of survival. "It's a very

fatal injury," he says. "A patient may die

from lack of oxygen or may bleed to death." Despite

newspaper headlines like WOUNDED TUPAC IS UNLIKELY TO

LIVE, family members hold out hope.

Day Seven: "This is Dale Pugh,

marketing and public relations director for the University

Medical Center," says a hospital hotline answering

machine. "This message is being recorded at approximately

5:15 p.m. on Friday, September 13. Tupac Shaku r has

passed away at UMC at approximately 4:03 p.m. Physicians

have listed the cause of death as respiratory failure

and cardiopulmonary arrest."

At the hospital there's a stillness, a

surreal calm. The contradictions of Tupac's many worlds

are converging. More than 150 people are gathered out

front: dark young girls and their mothers, lanky young

men with combs in their uncombed heads; others w earing

do-rags, professional women, young Native-American 'bangers

and children-dozens and dozens of children. Detached

reporters wait with the teary-eyed. A blond, blue-eyed

cop stands next to a white boy with dollar signs tattooed

on his neck.

Surrounded by family, Afeni dashes out

of the trauma unit, quiet determination etched on her

face. "She is an extremely spiritual person,"

says a family friend. "I think she knew. She had

given her only son to God long before this day."

A member of Tupac's crew leaves the trauma

room soon after. He stares down a hospital staffer and

screams: "Why the f*ck you let him die, yo?! Why

the f*ck you let him die?"

Behind him, Yakki, Tupac's cousin, who's

been at 'Pac's side since forever, walks out, red in

the face. Death Row artist Danny Boy comes in tube socks

and slippers, tears falling from behind half-and-half

glasses. He bends down on one knee as if in pra yer.

There's a trace of crimson in the clouds.

Suddenly three shining cars appear and Suge Knight steps

out of a black Lexus in a Phoenix Suns T-shirt, the

wound up top his head barely noticeable. His massive

figure quiets the crowd. He enters the trauma ce nter

hugging Danny Boy around the neck and talking quietly

with members of Tupac's family. Without his running

mate Tupac, Suge seems more solitary. After a few minutes

he turns to leave, taking pulls on a barely lit cigar

and leaving whispers in his wake .

As the minutes go by, an almost festive

atmosphere develops outside. Cars roll up bumping Tupac

songs. Children begin running beyond their mothers'

reach. One little boy in naps and slippers lies down

between two parked cars, glancing up mischievously to

check if anyone sees him.

The press packs it up. The crowd begins

to disperse. A black Humvee circles the hospital, blaring

"If I Die Tonight."

"I'll live eternal / Who shall

I fear / Don't shed a tear for me nigga / I ain't happy

here." The resoluteness in 'Pac's voice is cathartic.

"I hope they bury me and send me to my rest / Headlines

readin' murdered to death / My last breath...."

Such eerily prophetic lines were not unusual

for Tupac, who seemed to be rehearsing his death from

early on. For him, it was valor over violence, destiny

over death. But if his listeners were forewarned, they

were still unprepared. "Now it's real," say

s Vibe writer Robert Morales. "This scene has lost

its cherry. All the shit people have been talking in

the past five years, all the dissing and posturing,

has led to this. Hip hop has crossed a line, and it's

gonna be hard to cross back."

Back To Interviews

|